The art of thinking

A truly remarkable and one-of-a-kind work of nonfiction, Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid was first published in 1979, winning the Pulitzer Prize. In this overly stimulating and mind-blowing book, American scholar Douglas R. Hofstadter draws inspiration from music and mathematics to art and biology, while delving into elusive notions such as consciousness, self-reference, recursion, isomorphism, and “strange loops”, in order to investigate the deeper essence and nature of intelligence itself.

In his extensive and wide-ranging study of the inner workings of mind and cognitive processes, Hofstadter examines various properties of intelligence, such as being able to jump out of the system or breaking out of predetermined patterns. Especially appealing in Hofstadter’s approach is the way he constantly draws intriguing analogies from various fields of art in order to better illustrate complex notions and concepts.

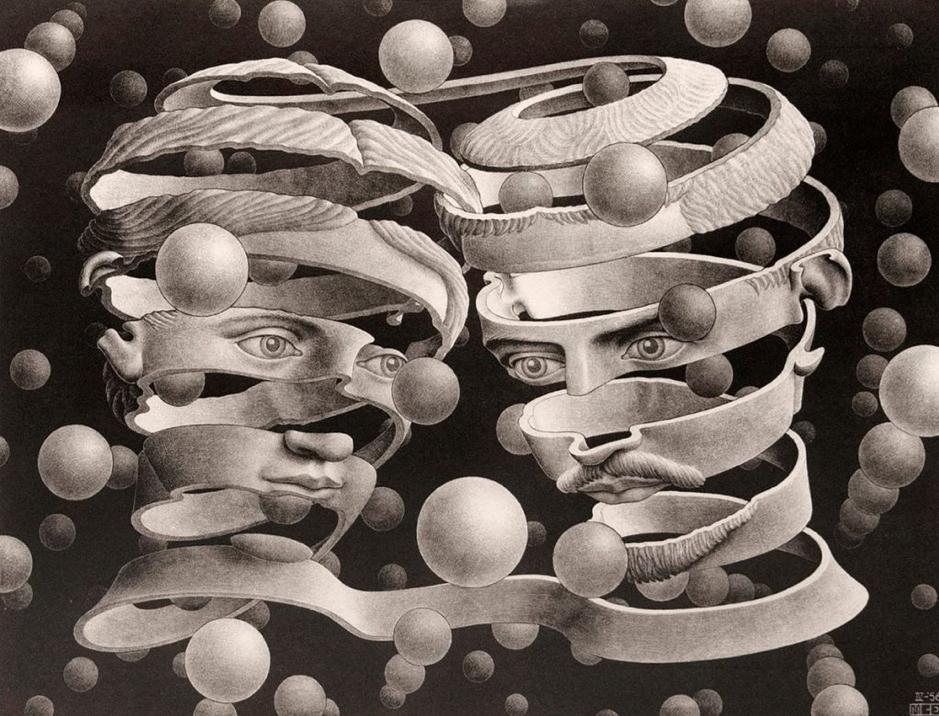

M.C. Escher, Bond of Union (1956). © The M.C. Escher Company, The Netherlands

Bach’s fugue in mind and space

Music, and specifically J.S. Bach’s music, is particularly prominent throughout the book as a vehicle through which Hofstadter offers many valuable insights about cognition, reasoning and creativity. “Intelligence loves patterns and balks at randomness”, he writes, while comparing Bach’s “self-contained” music with the random processes and aleatoric nature of John Cage’s works. As he puts it in a short but illuminating passage on codes and decipherment: “In form, there is content”.

In his landmark book, Hofstadter offers another beautiful analogy when he mentions “an inner tension, very much like the tension in a piece of music caused by chord progressions that let you know what the tonality is, without resolving. […] The mathematician’s sense of tension is intimately related to his sense of beauty, and is what makes mathematics worthwhile doing.” He also goes on to liken analogies to chords using the concept of an imaginary “keyboard of concepts”: superficially similar ideas – like physically close notes – are often not deeply related, whereas deeply related ideas are often superficially disparate, just like harmonically close notes are physically distant.

While discussing the cultural context and emotional appeal of music, Hofstadter wonders: “Will beings of an alien civilization have emotions? Will their emotions – supposing they have some – be mappable, in any sense, onto ours?” Questions such as this become particularly intriguing in relation to experiments like the Voyager Golden Record time capsule, a pair of two identical phonograph records included aboard the two Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977 that are still travelling through deep space carrying music from – among others – J.S. Bach.

In any case, music, as all art in general, retains its aura of mystique and sense of wonder. As Hofstadter puts it: “Do you really understand Bach because you have taken him apart? Or did you understand it that time you felt the exhilaration in every nerve of your body?”

AI, music, and creativity

In his discussion of computer-generated music, Hofstadter notes that “in most circumstances, the driving force behind such pieces is a human intellect, and the computer has been employed, with more or less ingenuity, as a tool for realizing an idea devised by the human. The program which carries this out is not anything which we can identify with. It is a simple and simple-minded piece of software with no flexibility, no perspective on what it is doing, and no sense of self.”

Indeed, as in the case of recent attempts to emulate the style of J.S. Bach with the help of ChatGPT and MIDI technology, it seems that technology is still in the service of human intellect, a tool rather than the guiding force behind the creative process. However, as technology evolves and AI becomes increasingly self-aware, Hofstadter suggests that there will come a time “to start splitting up one’s admiration: some to the programmer for creating such an amazing program, and some to the program itself for its sense of music.”

As he writes: “Creativity is the essence of that which is not mechanical. Yet every creative act is mechanical. […] Perhaps what differentiates highly creative ideas from ordinary ones is some combined sense of beauty, simplicity, and harmony.” It is exactly these qualities that will, in the long run, prove to be crucial: “AI, when it reaches the level of human intelligence – or even if it surpasses it – will still be plagued by the problems of art, beauty, and simplicity, and will run up against these things constantly in its own search for knowledge and understanding.”

The eclipse of man: A terrifying prospect

While attempting to crack the mysteries of consciousness and intelligence, Hofstadter’s penetrative analysis offers some deep revelations about our own human nature. “Contradiction is a major source of clarification and progress in all domains of life”, he argues, adding that “we all are bundles of contradictions, and we manage to hang together by bringing out only one side of ourselves at a given time.”

Moreover, the awareness of human fallibility and imperfection appears in sharp contrast to the rise of superintelligence. As Hofstadter put it in a recent interview: “It’s like a tidal wave that is washing over us in unprecedented and unimagined speeds… And, to me, it’s quite terrifying because it suggests that everything that I used to believe was the case is being overturned. […] It’s a very traumatic experience when some of your most core beliefs about the world start collapsing. Especially when you think that human beings are soon going to be eclipsed… It feels as if the entire human race is going to be eclipsed and left in the dust. Soon.”

Echoing the concerns of other important scholars and thinkers such as Geoffrey Hinton and Noam Chomsky, Hofstadter is cautious about AI-powered language models such as ChatGPT. As he wrote recently: “It makes no sense whatsoever to let the artificial voice of a chatbot, chatting randomly away at dazzling speed, replace the far slower but authentic and reflective voice of a thinking, living human being. [..] To fall for the illusion that vast computational systems “who” have never had a single experience in the real world outside of text are nevertheless perfectly reliable authorities about the world at large is a deep mistake, and, if that mistake is repeated sufficiently often and comes to be widely accepted, it will undermine the very nature of truth on which our society — and I mean all of human society —is based.”